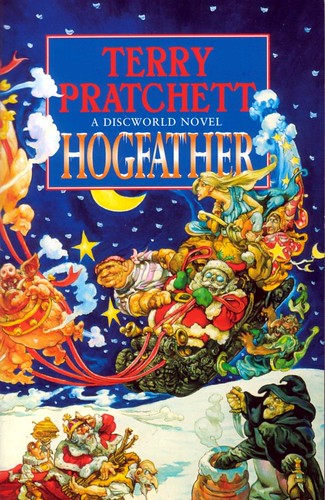

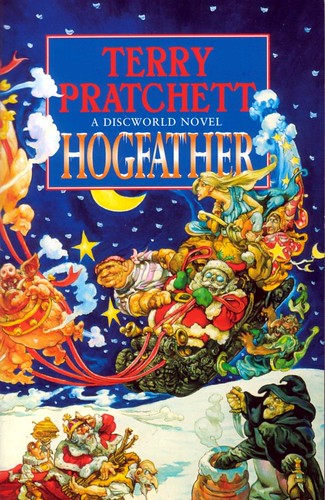

The cover was designed by

Josh Kirby, and should

give you some idea of the baroque nuttiness of it all.

Terry Pratchett's

Discworld novels might seem like a surprising leap from

yesterday's entry, but you should not be fooled by 600-odd years' having passed: Christmas is still around.

The great and wonderful thing about

Hogfather, however, is that it takes Christmas, shakes it, turns it upside down and twirls it around, and then places it before you sprinkled with teeth. In a good way, of course.

Pratchett writes what you might call ludic parody (from Latin

ludere: to play). It is playful; not mocking, but a friendly kind of poking at familiar patterns. What makes it all so wonderfully textured is precisely the fact that it is not a parody of one pattern, but that it draws together a variety of texts in order to create something new.

Having constructed the Discworld universe, Pratchett can then in turn use it as a backdrop for a series of shakings, turning-upside-downings and sundry similar treatments of other cultural patterns. This includes narrative conventions (the Disc's characters are well aware, for example, that an unarmed man facing an army has an unfair advantage; or that a one-in-a-million chance is the best shot at success); but it also serves as a backdrop for the historical and the political (with occasionally scathing social satire).

There are 40 novels set in the Discworld universe, and they make up a motley crew, which can be roughly organised according to groupings of characters like the Witches, the Watch, the Wizards; but one character shows up in nearly all of them, namely Death.

Hogfather is a book in the Death cycle, meaning that it not only has Death as a main character, but that it draws on and builds on the Death books that have preceded it, but can be read on its own. (Of course, if you read it on its own, you might lose out on some of the established texture.)

Death as a main character is rather less sinister than it sounds. Yes, he looks like a skeleton (or, as he is described in

Hogfather,

he's tall, not what you'd call fleshy, carries a scythe...

And he speaks in

small caps and separates people from their bodies. But an established aspect of Death as a character is his preoccupation with the human. Not the individual human, you will understand (though he is very friendly when he collects them), but rather the human condition. Which is why, when sinister forces are trying to make the world orderly and predictable by doing away with the messiness that the Hogfather brings to the world through his very existence, Death is the character that intervenes.

Well, Death and his estranged (reluctant) granddaughter (don't ask; read, and ye shall find), Susan Sto Helit, who is a governess with a penchant for realism.

She'd become a governess. It was one of the few jobs a known lady could do. And she'd taken to it well. She'd sworn that if she did indeed ever find herself dancing on rooftops with chimney sweeps she'd beat herself to death with her own umbrella.

You will, I am sure, catch the Mary Poppins reference. This is what Pratchett does. And this is why, while you may lose out on some Discworld texture if this is your first

Discworld book, you will still get the pleasurable thrill of recognition that is so integral to reading them.

And it is ultimately a Christmas story. One that is not about the baby Jesus and lambs galore, but one which picks up on the many other associations that float about the holiday. It is about presents, and fat men in red suits, and food (and more food) and drink, and revelry; but also in the background about death and renewal, and stories and blood. And teeth. It carries allusions like badges, expecting you to know your Christmas lore and recognizing it in

It was the night before Hogswatch. All through the house...

...one creature stirred. It was a mouse.

and in

"Did you check the list?" yes. twice. are you sure that's enough?

and in

The raven scratched its beak.

"The rat says... The rat says: you'd better watch out..."

But in between the Christmas bits, it continues to do the general shaking and turning upside-down that you would expect a Pratchett story to do. Like when Susan tells the children a fairytale:

“And then Jack chopped down what was the world's last beanstalk, adding murder and ecological terrorism to the theft, enticement, and trespass charges already mentioned, and all the giant's children didn't have a daddy anymore. But he got away with it and lived happily ever after, without so much as a guilty twinge about what he had done...which proves that you can be excused for just about anything if you are a hero, because no one asks inconvenient questions.”

or when Hex (the Discworld equivalent of a computer) states that

+++ Divide By Cucumber Error. Please Reinstall Universe And Reboot +++

which I believe we can all sympathise with on occasion.

I have consulted my conscience (Tor) and concluded that while you can read it over and over,

Hogfather is to some extent a rather spoilable novel (in that it weaves together a series of plot lines in a surprising way), and I would not want to deprive you of the pleasure of seeing it all come together for the first time. I will, however, point out that the moral of the tale is this:

"‘All right,’ said Susan. ‘I’m not stupid. You’re saying humans need… fantasies to make life bearable.’

really? as if it was some kind of pink pill? no. humans need fantasy to be human. to be the place where the falling angel meets the rising ape.

‘Tooth fairies? Hogfathers? Little—’

yes. as practice. you have to start out learning to believe the little lies.

‘So we can believe the big ones?’

yes. justice. mercy. duty. that sort of thing.

And just in case you still have doubts, here is a bonus dreadful pun from Death to you. With love.

let's get there and sleigh them. ho. ho. ho.

In a final bit of news, I gather you have all been very good, as

Good Omens is on radio this Christmas. If you have no idea what I am on about, we need to talk about some rather fundamental things.

Comments