Following

Tor's excellent example from a few years back, I've decided to give you a Calcuttagutta countdown to presents and family dinners. And because it is me doing it, I am doing it with books and short stories. CHRISTMAS books and short stories. And nothing says Christmas quite like a headless green man.

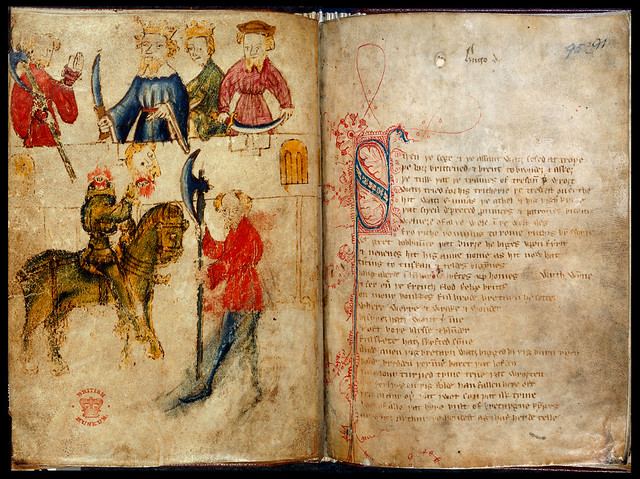

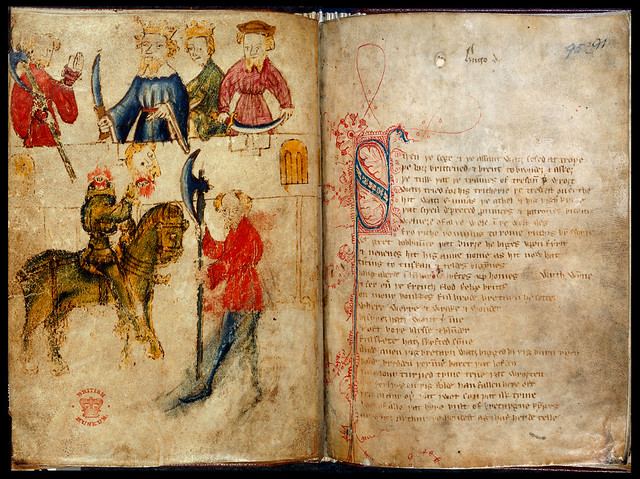

14th century manuscript from the British Library collection.

(click on image to get to British Library gallery, where you can explore it more fully)

"Sir Gawain and the Green Knight" is a 14th century poem, written by a contemporary of Geoffrey Chaucer (in either Edward III's or Richard II's reign, depending on who you ask). It opens on New Year's Day, but don't be fooled: it seems to me a classic midwinter tale, with the connotations of death and renewal which midwinter festivals like Christmas are all about; the middle part IS set at Christmas, and in addition the first line of the stanza below (from the opening of the poem) tells us that "this king [Arthur] lay at Camelot upon Christmas".

Þis kyng lay at Camylot vpon Krystmasse

With mony luflych lorde, ledez of þe best,

Rekenly of þe Rounde Table alle þo rich breþer,

With rych reuel oryȝt and rechles merþes.

Þer tournayed tulkes by tymez ful mony,

Justed ful jolilé þise gentyle kniȝtes,

Syþen kayred to þe court caroles to make.

For þer þe fest watz ilyche ful fiften dayes,

With alle þe mete and þe mirþe þat men couþe avyse;

Such glaum ande gle glorious to here,

Dere dyn vpon day, daunsyng on nyȝtes,

Al watz hap vpon heȝe in hallez and chambrez

With lordez and ladies, as leuest him þoȝt.

With all þe wele of þe worlde þay woned þer samen,

Þe most kyd knyȝtez vnder Krystes seluen,

And þe louelokkest ladies þat euer lif haden,

And he þe comlokest kyng þat þe court haldes;

For al watz þis fayre folk in her first age,

on sille,

Þe hapnest vnder heuen,

Kyng hyȝest mon of wylle;

Hit were now gret nye to neuen

So hardy a here on hille.

(This is not actually the opening of the poem. It both begins and ends with Troy, placing the story of Arthur, and thereby Gawain, in a larger context, something which you can also see in earlier versions of the Arthur myth. The excerpt does, however, give you an idea of the classic alliterative verse form, followed by the "bob and wheel" at the end: the very short line followed by four short, rhymed lines. But I digress.)

You should try reading the above out loud; I suspect you'll understand more than you expect. It is all about their Christmas revels, in the lead-up to the main action. King Arthur and his Knights of the Round Table are having a lovely time during a fifteen-day Christmas celebration, with food and jousting tournaments and ladies and dancing.

Arthur, however, will not eat until he is told a good story or someone has invited one of his knights to a daring joust or adventure (I am sure we can all identify), which is when a giant of a man enters (and a green one at that).

For wonder of his hwe men hade,

Set in his semblaunt sene;

He ferde as freke were fade,

And oueral enker-grene.

As if his complexion were not enough to get on with, (or the fact that his horse is equally green, or that he grasps holly with one hand and a giant axe in the other,) he then goes on to ask for the bravest of men to strike at him with that axe, and that he be allowed to return the blow in a year and a day.

While the other knights are busy staring at him as if he is mad, Gawain takes it on; and as the Green Knight kneels, he cleanly cuts off his head; whereupon the now headless Green Knight picks it up and tells him he'll see him in a year's time to return the blow.

Arthur declares that

Wel bycommes such craft vpon Cristmasse

and they finally sit down to eat.

The plot, of course, is just getting started. The following year, Gawain keeps his word and sets out in search of the Green Knight. He travels through the snow and ice, and as he crosses himself three times, a great castle appears, surrounded by a green park. Very mysterious. (And, incidentally, on Christmas Eve.) Gawain, not generally one to overthink things, happily accepts the hospitality of the lord of the castle, Bertilak de Hautdesert, who promises to take him to the Green Knight in time to fulfill his promise.

First, though, he proposes they play a game. Each day the host will leave for the hunt, and each evening he will give Gawain what he has caught, if Gawain will do the same in exchange. Each day Bertilak hunts a different animal; and while he is gone Bertilak's wife throws herself with increasing insistence at Gawain.

The first day Gawain wakes up to find Bertilak's wife in his bed, but being a good and virtuous knight, he gives her a kiss and sends her on her way. Bertilak returns, gives him a deer and gets the kiss in return (though Gawain does not tell him where he got it).

The following day, this is repeated, though the lady is more scantily clad. Still resisting (though finding it difficult, because he really doesn't want to be rude), Gawain gets another kiss; and when Bertilak returns with a wild boar, he once more passes on the kiss.

On the third day, Gawain must once again resist the temptations of the lady. And he does it admirably, with one exception. She gives him a girdle to remember her by, claiming that it will protect him against the blow of the Green Knight. When her husband returns, gifting him a sly fox, Gawain keeps the girdle back.

Meeting the Green Knight on the following day, Gawain is of course roundly warned, and his companion promises not to tell anyone if should decide to run away. Gawain rejects cowardice, however, and keeps his promise: He takes off his helmet and kneels to receive the blow. At the first strike of the axe, Gawain flinches and is roundly mocked; at the second, he stays still but the Knight still misses. Finally, the third strike nicks his neck, and Gawain declares the game over and done with.

The Green Knight now reveals himself to be Bertilak, explaining that the two blows that missed were for Gawain's steadfastness in resisting the very insistent lady of the castle; the third nicked him because he concealed the girdle.

Then follows a list of how women are always to blame for the failures of men (with the advice to "love them well and believe them not"). And it turns out Morgan Le Fay is behind it all (surprise, surprise), in a dastardly attempt to shame King Arthur and his knights; a plot Gawain has foiled by his (generally high standard of) chivalry.

As Gawain tries to return the girdle, the Knight/Bertilak tells him to keep it, as a sign of his chivalry and honourable behaviour in this grand adventure. Gawain, rather more self-flaggelating, says he will bear it till the end of his days, but as a sign of his failure to be perfectly chivalrous.

When he arrives back at the court of King Arthur, however, the king and all his knights seem rather more taken with the honour idea, and all the knights vow they will carry identical green girdles, making it a sign of chivalry. The story is often tied to the origins of the Order of the Garter (a garter being not unlike a girdle in associative terms), and as you may know, the Order of the Garter carries the inscription

"Honi soit qui mal y pense", which means "Shame to him who thinks ill of it" (which suits the ending to the tale rather well). This motto is in fact written at the end of the manuscript, but from what I can find out it is probably a later addition. (In fact, if anyone is looking for a Christmas gift idea for me,

this book looks very interesting.)

A final point of interest: Tolkien edited an edition of this poem, originally published in 1925, which remained highly influential for a long time. He also translated it, at a later point. You will be surprised to find, I am sure, that both can be acquired in exchange for something as common as money.

Comments